Urban oases – from the city to your living room

In many cities, the roads are leading back to nature: green spaces are popping up in parks and courtyards, on terraces, roofs and building façades. In a sea of urban grey, green is more than just beautiful. It is an investment in the well-being of city dwellers and in the environment.

Lunch in the park, an after-work stroll along the lake, a Sunday hike through nearby woods. To hear birdsong, to enjoy the views of nature, to decompress. There, surrounded by natural beauty, we breathe in and fill up with energy. For many of us, the importance of green spaces in cities took on new importance through the COVID-19 pandemic. Green outdoor areas became places to escape after a long day, offering a bit of variety to balance the tediousness of working from home. Balconies, parks and courtyards were the only places left for meeting with others and socialising. The benefits of plants and green landscapes also proved alluring during this time. Numerous psychological studies have proven the positive effects of nature on the psyche. Green spaces mean regeneration for the mind and body.

Stress and the city

This is especially relevant as more and more of us take to cities. More than half of the world’s population now lives in urban areas. The United Nations forecasts that, by 2050, more than two thirds of us will live in urban areas. City dwellers, however, are at higher risk of psychological disorders. The research of Berlin-based psychiatrist and stress researcher Prof. Mazda Adli indicates that the likelihood of succumbing to depression is 1.5 times larger in cities. Anxiety disorders appear 1.2 times as frequently. A clear difference is seen in cases of schizophrenia: the risk for urban dwellers is twice as high as for those in rural areas. Adli attributes this to the higher stress levels to which urban dwellers are subjected. He calls this form of stress "social stress", describing it as the product of social density combined with social isolation. Too many people in close quarters, but nevertheless lonely. What do cities need to make them worth living in and keep their inhabitants from falling ill?

Urban green spaces for well-being

Open spaces and green areas play a decisive role in the shaping of a city and the quality of life it offers. Urban oases help people to dispel personal stress for physical and mental regeneration. However, these alone will not eliminate social stress. A healthy and vibrant city needs green spaces for leisure, but also meeting spaces that facilitate social interaction. Places for stimulation and interaction are just as important as those that offer relaxation and solitude. Public green spaces should invite people to go out and meet others. The events, meet-ups and various forms of social contact they encourage counteract the social isolation that many city dwellers experience. Sustainable and forward-thinking urban planning means allowing for uses across a variety of demographic groups as well as across generations. Parks for relaxation, playgrounds or recreation areas used by both young and old alike, urban gardens where city dwellers plant vegetables together. The cities of tomorrow are places where the health and well-being of their inhabitants are actively promoted by their urban structures and architecture.

Hot, hotter, hottest

These positive effects of nature on humans are known as ecosystem services. The use of vegetation in urban environments offers many such benefits. Of special relevance are those that help to tackle challenges like climate change and urbanisation. According to the Federal Office for the Environment, the rising temperatures in cities and metropolitan areas is a direct result of climate change. CH2018 climate scenarios indicate that, by 2050, Switzerland will face increasingly long, dry summers, but also regular heavy precipitation. Urban centres face the biggest challenges, where paved surfaces, poor air circulation, lack of shade, and traffic and industrial exhaust cause heat to accumulate. Surfaces like glass reflect the sunlight, whilst concrete, asphalt and building surfaces retain heat. In summer, dense construction and the lack of air corridors turn cities into pockets of heat. This, known as the "urban heat island effect", can make cities several degrees warmer than their surrounding areas. At the same time, it is more difficult for rainwater to run off from built-up, paved or otherwise sealed surfaces, resulting in overloaded sewage pipes and flooded streets and cellars. But it's not too late: builders, architects and urban planners are finding ways to address these issues by bringing nature and cities into harmony.

For a better urban climate and more biodiversity

Green spaces have a significant impact on urban microclimates. Urban vegetation can reduce temperatures by providing shade, cooling through evaporation and absorbing the sun's rays so that building façades and their interiors stay cooler. Another important ecosystem service is that the vegetation in urban green spaces binds CO2 whilst producing oxygen. In addition, plants filter dust and contaminants from the air, helping to improve air quality. An immense advantage in light of the high volume of traffic and airborne particulate pollution in cities. Green areas help to hold rainwater in times of heavy precipitation, acting as relieving buffers for urban sewage systems. And: the more green sites and vegetation present, the more sounds are dampened, thus reducing noise levels – and that's just as beneficial for human inhabitants as it is for the many bird and insect species thus able to reclaim their old habitats.

Going up

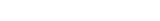

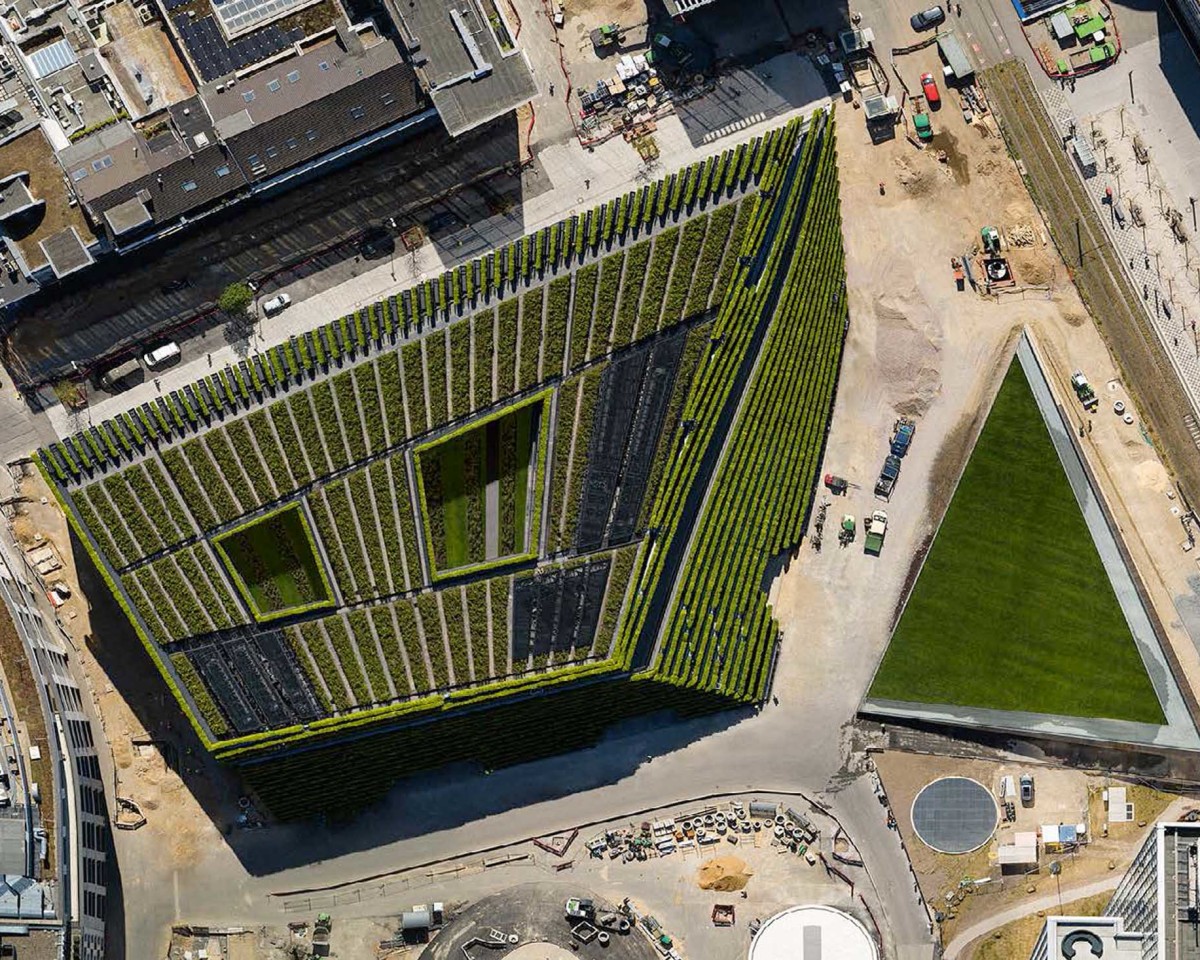

What happens when room for development is scarce? Architects are responding to this problem with new forms of landscaping that relocate gardens, trees, shrubs and lawns to other places. Green buildings are being designed all over the world – with plants on their façades, roofs, terraces and balconies. Car parks, shopping centres, tramways and administration buildings have become the new showcases of urban greenery. In urban areas where a lack of space forces construction in a vertical direction, vegetation is simply coming along with it. The visual appeal of green façades has resulted in their being used by urban planners and architects as a "quick fix" – one that is attractive but far too costly to maintain, leading to an even greater increase in the price of urban residential space. Sustainable green façades require professional planting appropriate to the specific conditions and affordable maintenance to make green walls not only attractive and climate friendly, but also welcomed by homeowners and tenants.

Vertical gardens

Cities are sporting more and more green roofs. Here, too, the marriage of plants and architecture provides both beauty and function. The plants on the roofs use the rainwater collected in the substrate to grow. The evaporation of this water cools the environment in summer. In winter, the roof vegetation acts as insulation. It also protects the roof structure from the elements and can even double its life expectancy. And that's practical.

Urban green roofs are practical in another way: they provide the inhabitants with a place to tend gardens. Small herb gardens on balconies are being supplemented by vegetable garden beds on urban rooftops with space for growing food. The roof of the Paris Expo Porte de Versailles exhibition centre currently holds a giant rooftop farm – even said to be the largest in the world. Large-scale projects like this are referred to as "vertical farming"; on a smaller scale, it's known as "urban gardening." Urban gardens are food sources and leisure spots in one. These new oases of tranquillity are increasingly becoming an important element of stress reduction. They foster neighbourly interaction and contribute to liveable residential communities.

Liaison between architecture and nature: in recent years, more and more architects all over the world have been incorporating plants into their building designs.

Green homes

We not only feel the need for green oases in the city, but in our homes as well. In Switzerland, people spent more time in gardens last year than ever before: gardens are booming, independent of space and budget. An analysis by prontopro.ch, an online service portal, shows that the demand for gardening and plant care services has grown 27% since the first lockdown. People are spending money on their houses and gardens instead of on travel. Whilst the upturn in house plants comes as no surprise, plants in interior spaces are also known to improve air quality, increase well-being and help to reduce stress.

Whether in personal living spaces or out in city squares, we can't seem to get enough green. Ideally, we'll soon be enjoying it again together with others – lunches in the park, day trips in the country and backyard barbecues.

Switzerland’s loveliest urban oases

Kannenfeldpark, Basel

With its 9-hectares of parkland, Basel’s Kannenfeldpark is the largest park in the city. This expansive green space holds over 800 trees. Its size and its circular path make it an ideal park for joggers and walkers. It also holds numerous recreational areas with playground equipment, a wading pool, a kiosk, various art objects and a rose garden.

The Camellia Park, Locarno

The splendid Parco delle Camelie in Locarno boasts over 850 camellia species spread over 10,000 square metres: perfect for flower fans, nature lovers and those seeking a quiet place to relax. The park is divided into numerous flower beds and designed as a sort of labyrinth. Here, visitors will find two ponds with fountains, an information pavilion and a small amphitheatre providing a welcome place to sit and enjoy a wonderful view of Lago Maggiore.

The Old Botanical Garden, Zurich

This enchanting oasis, located in Zollikerstrasse in central Zurich, offers quiet surroundings and gorgeous views – and is just a 12-minute walk from the main station. This hill in the heart of the city was once a bulwark for its defence. The garden, laid out in 1837, features many exotic old trees. It also contains a mediaeval herb garden, an octagonal palm house built in 1851 and numerous hidden places offering rest and relaxation.

The "Guggihügel", Zug

Just a few steps from the historic town centre, the "Guggi" offers breathtaking views of the city. It's well worth the short ascent that starts behind the old post office building: the Guggihügel is a small oasis in the heart of the city. The star, however, is the view of the old historic district with its towers, fortress and churches against a backdrop of glittering lake and majestic mountains. Sunsets from the Guggihügel are legendary.

The impact of climate change on the selection and care of plants

The Alps form a natural climate and vegetation barrier. Climate change is altering this barrier and the conditions that go with it. Garden plant species that grow well today may have difficulties 20 years hence due to increasing temperatures. The rise in temperatures affects the development stages of plants and leads to decay and mineralisation, and thus a decline in carbon stocks in the soil. These are factors that must be considered when selecting and installing plants.

The southern canton of Ticino is already feeling these effects, as higher temperatures predominate here in comparison to the rest of Switzerland. Simone Acerbis, director of Acerbis Paesaggistica SA, a garden and landscaping company in Bedano, is quite familiar with this issue. Acerbis worked together with Alfred Müller AG on the construction of the Residenza IN Centro development in Mendrisio. When selecting plants, he especially looks for species that can withstand the higher temperatures in Ticino but are not considered on the north side of the Alps.

Acerbis says that, in the future, the most suitable plants will be those that can thrive despite extreme weather conditions. "It’s important to have a mix of plants that are suitable for the location. The wind and soil conditions must be taken into account, as well as sun, moisture and precipitation. The right assortment of plants may even improve soil fertility. Consultation and planning with a professional company is therefore key. Professional planting and regular, professional maintenance will extend the life expectancy of the flora and ensure that any problems are caught early."